INTERVIEW, 1966

QUESTIONER: It's interesting that the photographic image you've worked from most of all isn't a scientific or a journalistic one but a very deliberate and famous work of art- the still of the screaming nanny from Potemkin.

PAINTER: It was a film I saw almost before I started to paint, and it deeply impressed me--I mean the whole film as well as the Odessa Steps sequence and this shot. I did hope at one time to make-it hasn't got any special psychological significance I did hope one day to make the best painting of the human cry. I was not able to do it and it's much better in the Eisenstein and there it is. I think probably the best human cry in painting was made by Poussin....

Q: You've used the Eisenstein image as a constant basis and you've done the same with the Velazquez Innocent X, and entirely through photographs and reproductions of it. And you've worked from reproductions of other old master paintings. Is there a great deal of difference between working from a photograph of a painting and from a photograph of reality?

P: Well, with a painting it's an easier thing to do, because the problem's already been solved.. The problem that you're setting up, of course, is another problem. I don't think that any of these things that I've done from other paintings actually have ever worked....

Q: I want to ask whether your love of photographs makes you like reproductions as such. I mean, I've always had a suspicion that you're more stimulated by looking at reproductions of Velizquez or Rembrandt than at the originals.

P: Well, of course, it's easier to pick them up in your own room than take the journey to the National Gallery, but I do nevertheless go a great deal to look at them in the National Gallery, because I want to see the colour, for one thing. But, if I'd got Rembrandts here all round the room, I wouldn't go to the National Gallery...

Q: Up to now we've been talking about your working from photographs which were in existence and which you chose. And among them there have been old snapshots which you've used when doing a painting of someone you knew. But in

recent years, when you've planned to do a painting of somebody, I believe you've tended to have a set of photographs taken especially.

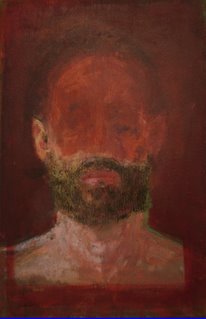

P: I have. Even in the case of friends who will come and pose. I've had photographs taken for portraits because I very much prefer working from the photographs than from them. It's true to say I couldn't attempt to do a portrait from

photographs of somebody I didn't know. But, if I both know them and have photographs of them, I find it easier to work than actually having their presence in the room. I think that, if I have the presence of the image there, I am not able to drift

so freely as I am able to through the photographic image. This may be just my own neurotic sense but I find it less inhibiting to work from them through memory and their photographs than actually having them seated there before me.

Q: You prefer to be alone?

P: Totally alone. With their memory.

Q: Is that because the memory is more interesting or because the presence is disturbing?

P: What I want to do is to distort the thing far beyond the appearance, but in the distortion to bring it back to a recording of the appearance.

Q: Are you saying that painting is almost a way of bringing somebody back, thatthe process of painting is almost like the process of recalling?

P: I am saying it. And I think that the methods by which this is done are so artificial that the model before you, in my case, inhibits the artificiality by which this thing can be brought back.

Q: And what if someone you've already painted many times from memory and photographs sits for you?

P: They inhibit me. They inhibit me because, if I like them, I don't want to practise before them the injury that I do to them in my work. I would rather practise the injury in private by which I think I can record the fact of them more clearly.

Q: in what sense do you conceive it as an injury?

P: Because people believe--simple people at least--that the distortions of them are an injury to them--no matter how much they feel for or how much they like you.

Q: Don't you think their instinct is probably right?

P: Possibly, possibly. I absolutely understand this. Nut tell me, who today has been able to record anything that comes across to us as a fact without causing deep injury to the image?

Q: Is it a part of your intention to try and create a tragic art?

P: No. Of course, I think that, if one could find a valid myth today where there was the distance between grandeur and its fall of the tragedies of Aeschylus and Shakespeare, it would be tremendously helpful. But when you're outside a tradition, as

every artist is today, one can only want to record one's own feelings about certain situations as closely to one's own nervous system as one possibly can. But in recording these things I may be one of those people who want the distances between what used to be called poverty and riches or between power and the opposite of power.

Q: There is, of course, one great traditional mythological and tragic subject you've painted very often, which is the Crucifixion.

P: Well, there have been so very many great pictures in European art of the Crucifixion that it's a magnificent armature on which you can hang all types of feeling and sensation. You may say it's a curious thing for a nonreligious person to take the

Crucifixion, but I don't think that that has anything to do with it. The great Crucifixions that one knows of--one doesn't know whether they were painted by men who had religious beliefs....

Q: It seems to be quite widely felt of the paintings of men alone in rooms that there's a sense of claustrophobia and unease about them that's rather horrific. Are you aware of that unease?

P: I'm not aware of it. But most of those pictures were done of somebody who was always in a state of unease, and whether that has been conveyed through these pictures I don't know. But I suppose, in attempting to trap this image, that, as this man was very neurotic and almost hysterical, this may possibly have come across in the

paintings. I've always hoped to put over things as directly and rawly as I possibly can, and perhaps, if a thing comes across directly, people feel that that is horrific. Because, if you say something very directly to somebody, they're sometimes offended, although it is a fact. Because people tend to be offended by facts, or what used to be called truth.

Q: On the other hand, it's not altogether stupid to attribute an obsession with horror to an artist who has done so many paintings of the human scream.

P: You could say that a scream is a horrific image; in fact, I wanted to paint the scream more than the horror. I think, if I had really thought about what causes somebody to scream, it would have made the scream that I tried to paint more successful. Because I should in a sense have been more conscious of the horror that produced the scream. In fact they were too abstract.... I think that they come out of a desire for ordering and for returning fact onto the nervous system in a more violent way. Why, after the great artists, do people ever try to do anything again? Only because, from generation to generation, through what the great artists have done, the instincts change. And, as the instincts change, so there comes a renewal of the feeling of how can I remake this thing once again more clearly, more exactly, more violently. You see, I believe that art is recording. I think it's reporting. And I think that in abstract art, as there's no report, there's nothing other than the aesthetic of the painter and his few sensations. There's never any tension in it.

Q: You don't think it can convey feelings?

P: I think it can convey very watered-down lyrical feelings, because I think any shapes can. But I don't think it can really convey feeling in the grand sense... I think it's possible that the onlooker can enter... into an abstract painting. But then

anybody can enter more into what is called an undisciplined emotion, because, after all, who loves a disastrous love affair or illness more than the spectator? He can enter into these things and feel he is participating and doing something about it. But that of course has nothing to do with what art is about. What you're talking about now is the

entry of the spectator into the performance, and I think in abstract art perhaps they can enter more, because what they are offered is something weaker which they haven't gotto combat.

Q: If abstract paintings are no more than pattern-making, how do you explain the fact that there are people like myself who have the same sort of visceral response to them at times as they have to figurative works?

P: Fashion.

Q: You really think that?

P: I think that only time tells about painting. No artist knows in his own lifetime whether what he does will be the slightest good, because I think it takes at least seventy- five to a hundred years before the thing begins to sort itself out from the

theories that have been formed about it. And I think that most people enter a painting by the theory that has been formed about it and not by what it is. Fashion suggests that you should be moved by certain things and should not by others. This is the reason that even successful artists--and especially successful artists, you may say--have no idea

whatever whether their work's any good or not, and will never know.

Q: Not long ago you bought a picture ...

P: By Michaux.

Q: . . . by Michaux, which was more or less abstract. I know you got tired of it in the end and sold it or gave it away, but what made you buy it?

P: Well, firstly, I don't think it's abstract. I think Michaux is a very, very intelligent and conscious man, who is aware of exactly the situation that he is in. And I think that he has made the best tachiste or free marks that have been made. I think he is much better in that way, in making free marks, than Jackson Pollock.

Q: Can you say what gives you this feeling?

P: What gives me the feeling is that it is more factual: it suggests more. Because after all, this painting, and most of his paintings, have always been about delayed waysof remaking the human image, through a mark which is totally outside an illustrational mark but yet always conveys you back to the human image--a human image generally

dragging and trudging through deep ploughed fields, or something like that. They are about these images moving and falling and so on.

Q: Are you ever as moved by looking at a still life or a landscape by a great master as you are by looking at paintings of the human image? Does a Cezanne still life or landscape ever move you as much as a Cezanne portrait or nude? ...

P: Certainly landscapes interest me much less. I think art is an obsession with life and after all, as we are human beings, our greatest obsession is with ourselves. Then possibly with animals, and then with landscapes.

Q: You're really affirming the traditional hierarchy of subject matter by which history painting--painting of mythological and religious subjects--comes top and then portraits and then landscape and then still life.

P: I would alter them round. I would say at the moment, as things are so difficult, that portraits come first.

Q: In fact, you've done very few paintings with several figures. Do you concentrate on the single figure because you find it more difficult?

P: I think that the moment a number of figures become involved, you immediately come on to the storytelling aspect of the relationships between figures. And that immediately sets up a kind of narrative. I always hope to be able to make a great

number of figures without a narrative.

Q: As C6zanne does in the bathers?

P: He does....

Q: Talking about the situation in the way you do points, of course, to the very isolated position in which you're working. The isolation is obviously a great challenge, but do you also find it a frustration? Would you rather be one of a number of artists

working in a similar direction?

P: I think it would be more exciting to be one of a number of artists working together, and to be able to exchange.... I think it would be terribly nice to have someone to talk to. Today there is absolutely nobody to talk to. Perhaps I'm unlucky and don't know those people. Those I know always have very different attitudes to what I have. But I think that artists can in fact help one another. They can clarify the situation to one another. I've always thought of friendship as where two people really tear one another apart and perhaps in that way learn something from one another.

Q: Have you ever got anything from what's called destructive criticism made by critics?

P: I think that destructive criticism, especially by other artists, is certainly the most helpful criticism. Even if, when you analyze it, you may feel that it's wrong, at least you analyze it and think about it. When people praise you, well, it's very pleasant to be praised, but it doesn't actually help you.

Q: Do you find you can bring yourself to make destructive criticism of your friends' work?

P: Unfortunately, with most of them I can't if I want to keep them as friends.

Q: Do you find you can criticize their personalities and keep them as friends?

P: It's easier, because people are less vain of their personalities than they are of their work. They feel in an odd way, I think, that they're not irrevocably committed to their personality, that they can work on it and change it, whereas the work that has

gone out--nothing can be done about it. But I've always hoped to find another painter I could really talk to--somebody whose qualities and sensibility I'd really believe in-who really tore my things to bits and Whose judgement I could actually believe in. I envy very much, for in- stance, going to another art, I envy very much the situation when Eliot and Pound and Yeats were all working together. And in fact Pound made a kind of Caesarean operation on The Waste Land; he also had a very strong influence on Yeats--although both of them may have been very much better poets than Pound. I think it would be marvellous to have somebody who would say to you, "Do this, do that, don't do this, don't do that!" and give you the reasons. I think it would be very helpful.

Q: You feel you really could use that kind of help?

P: I could. Very much. Yes, I long for people to tell me what to do, to tell me where I go wrong.

Iscriviti a:

Commenti sul post (Atom)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento